LECTURE AND SLIDE SHOW

REFERENCES

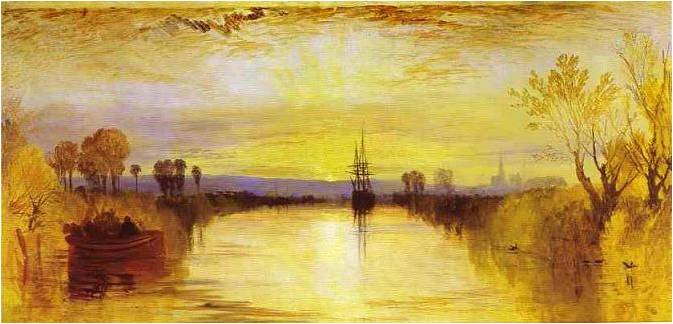

Description: Mount Tambora, a stratovolcano in Sumbawa, Indonesia became highly active in 1812 and erupted again on April 5th and April 10th, 1815. The major blast on the 10th was heard from 1,600 miles away and was thought to be the sound of firing cannonade. The eruption was four times larger than Krakatoa's in 1883. Pyroclastic flows spread at least 12 miles from the summit and killed an estimated 10,000 people. The eruption column reached the stratosphere - at an altitude of more than 140,000 feet. The coarser ash particles fell one to two weeks after the eruptions, but the finer ash particles stayed in the upper atmosphere from a few months up to a few years. Longitudinal winds spread these fine particles around the globe, creating optical phenomena that bore prolonged and brilliantly colored sunsets. The unusual climatic aberrations of 1816 had the greatest effect on the Northeastern United States, New England, the Canadian Maritimes, Newfoundland and Northern Europe.

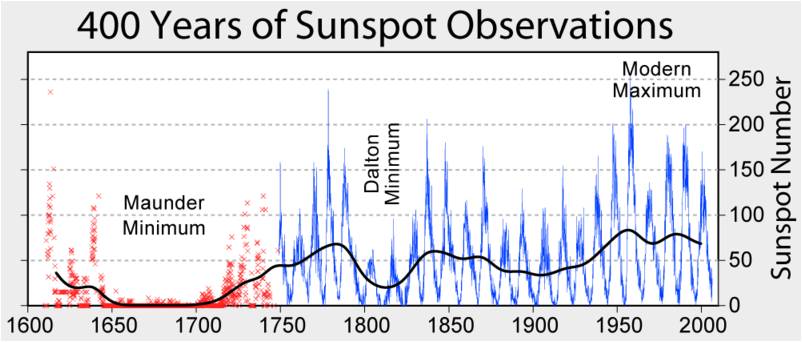

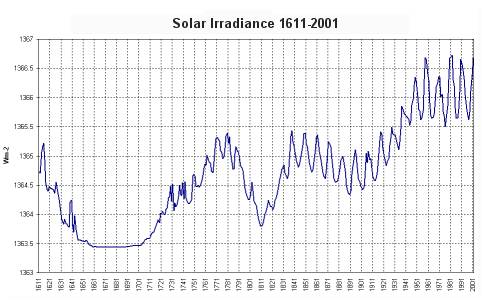

But there were two other factors, that factored with the Tambora eruption, caused sensational unseasonable temperature drops around the world. Sustained periods of weak magnetic activity make the Sun slightly dimmer, so Earth receives less solar light energy. The years 1812-15 were nearly ‘spotless’. The year 1816 had a rash of sunspots in the Spring with two major periods of solar activity - from May 3rd through May 10th, 1816 and again on June 11th, 1816. These could easily be seen with the naked eye at sunset. Many attributed the dank weather to the sunspots due to “lessening the amount of sunlight that was reaching the earth” – which was, of course, the opposite result. Solar irradiance actually increases with sunspot activity.

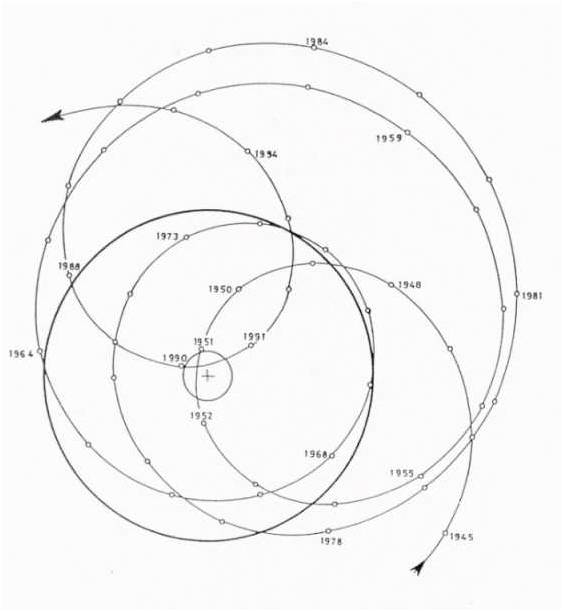

A third factor was 'inertial solar motion' - which is the shifting of the sun's position within our solar system in relation to the earth's revolution around the sun.

The temperature shifts were dramatic. In May 1816, frost killed off most of the crops that had been planted in New England. In June, two large snowstorms in eastern Canada and New England resulted in many human deaths. Nearly a foot of snow was observed in Quebec City in early June, with the consequential loss of crops. The result was regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality — in short, famine.

In July and August, lake and river ice was observed as far south as Pennsylvania. Rapid, dramatic temperature swings were common, with temperatures sometimes reverting from normal or above-normal summer temperatures (as high as 95 °F) to near-freezing within hours.

Even though farmers south of New England did succeed in bringing some crops to maturity, maize and other grain prices rose dramatically. Those areas suffering local crop failures had to deal with the lack of roads in the early 19th century, which prevented easy importation of bulky food stuffs. Many New England farmers were wiped out and tens of thousands struck out for the richer soil and better growing conditions of the Upper midwest (then the Northwest Territory). The winter of 1816-17 was brutal. There were luminous (electrical) snowstorms (‘thundersnow’) in Vermont in January and February of 1817 where ball lighting shocked many people.

Join historical astronomer and weather historian John Horrigan as he takes you through the "Year Without a Summer" and parallels it with the current aberrational weather conditions and dormant sunspot period.

THIS LECTURE HAS BEEN PERFORMED FOR:

Running Time: 1 hour and 7 minutes Size: 70 MB

Running Time: 1 hour, 22 minutes Size: 78 MB

ADDITIONAL AUDIO RECORDINGS:

THE LUMINOUS SNOW STORM OF 1895

Recorded on December 14, 2008 at Watertown, Massachusetts. John reads from Jerome Clark's Unnatural Phenomena about a "luminous" snow storm ("a shower of cold fire") encountered by a military officer who scales Pike's Peak in Colorado. 1 minute and 51 seconds; 2 MB

THE ENIGMA OF SNOW FIRE (1817 and 1845)

Recorded on December 15th, 2008 in Watertown, Massachusetts about two "snow fires" (luminous snow storms): one that took place in 1817 and another that happened in 1845. Running Time is 5 minutes. Size is 3 MB.

THE GREAT LUMINOUS SOLAR STORM OF 1823

Recorded on December 14, 2008 at Watertown, Massachusetts. John reads about two independent witnesses who corroborate a large solar protuberance on December 1st, 1823. 1:36; 2 MB

THE AURORA BOREALIS OF 1818

Recorded on December 14, 2008 at Watertown, Massachusetts. John reads about sailors who witness a bright and vivid aurora borealis in November of 1818 where a compass could be read on deck due to the luminosity. 1:33; 2 MB

THE GREAT LUMINOUS SNOW STORM OF 1817

Recorded on December 20, 2008 (during a blizzard) at Watertown, Massachusetts. John reads from David Ludlum's Early American Winters I and gives the most complete account (by reading the original testimony of John Farrar) ever recorded concerning the Great Luminous Snow Storm of January 17th, 1817. 8 minutes and 35 seconds; 9 MB

THE LUMINOUS SNOW STORM OF 1817

Recorded on December 14, 2008 at Watertown, Massachusetts. John reads from Extreme Weather about a "Luminous" snow storm (i.e. "snow fire") that struck northern New England on January 17th, 1817. 2 minutes and 54 seconds; 3 MB

THE ELECTRICAL SNOW STORM OF 1817

Recorded on December 14, 2008 at Watertown, Massachusetts. John reads about various "luminous" snow storms including one in both January and March of 1817. There is also an account of an electrical thunderstorm in Woburn, Massachusetts in July of 1771 that causes a man to be electrified. 2 minutes and 55 seconds 3 MB

THE GREAT AURORA BOREALIS OF AUGUST, 1817

Recorded on December 14, 2008 at Watertown, Massachusetts. John reads about a spectacular aurora borealis that was closely observed from the Shetland Islands in August of 1817. 3:42 3 MB

THE AURORA BOREALIS OF SEPTEMBER, 1817

Recorded on December 14, 2008 at Watertown, Massachusetts. John reads about a vivd aurora borealis that was observed and heard from the Shetland Islands on September 6th, 1817. 2:03; 2 MB

THE LUMINOUS SNOW STORM OF 1813

Recorded on December 14, 2008 at Watertown, Massachusetts. John reads about a luminous snowstorm in Scotland that fell in March of 1813. 56 seconds; 1 MB

THE "BACKWARD SPRINGS" OF VERMONT (1789 - 1817)

Recorded on July 9, 2007 at Watertown, Massachusetts. John reads from David Ludlum's Vermont Weather Book about several snow storms during the month of May in Vermont during "the cold years" from 1789 through 1817. 2 minutes and 23 seconds; 2 MB

A CHRONOLOGY OF LUMINOUS WEATHER (1788 - 1895)

Recorded on December 15th, 2008 in Watertown, Massachusetts about a chronology of luminous electrical snow storms in the 19th century in the Northeastern United States, including the famous "luminous snow storm" of 1817 in Vermont and New Hampshire. Running Time is 5 minutes. Size is 5 MB.

RETURN TO JOHN HORRIGAN HISTORICAL LECTURES

JOHN'S AUDIO CATALOGUE